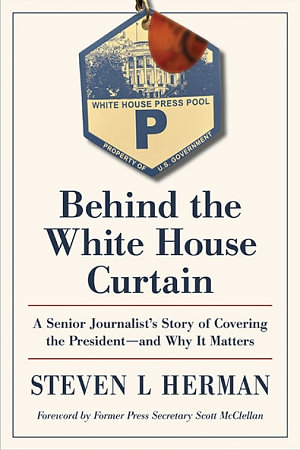

In this episode of "Democracy Nerd", host Jefferson Smith interviews Steven L. Herman--the Chief National Correspondent for Voice of America and the author of "Behind the White House Curtain: A Senior Journalist's Story of Covering the President--and Why It Matters"--about the importance of unbiased information to ensure a healthy and peaceful democracy.

Jefferson and Steven discuss the history and importance of Voice of America, a government-funded international broadcast platform, whose mission is to provide news and accurate information about the United States to global audiences, with an overall goal to promote understanding and goodwill between the U.S. and other countries. To ensure Voice of America accomplishes its mission, a firewall is created to ensure political interference by presidential administrations on VOA's independent content doesn't occur. However, during the Trump presidency, attempts were made to politicize VOA's content. Steven emphasizes the importance of VOA to maintain independence from political influence and take the necessary steps to ensure its reporting remains objective and free from partisan bias.

Steven also discusses the difficulties faced by journalists who rely on social media to collect facts in an era of widespread disinformation and misinformation. Fact-checking and verifying info is an essential duty performed by journalists that fall by the wayside in a rush for breaking news or to spin events in support of a political agenda. Steven shared his experiences live Tweeting from Fukushima after the disastrous 2011 earthquake, and continued to regularly use Twitter for the next 15 years before receiving a lifetime ban in 2022.

Overall, this episode sheds light on the challenges journalists face in maintaining journalistic integrity, navigating social media, and ensuring accurate information reaches the public.